Jinn Ginnaye, 2014-pres

Jinn-Ginnaye is a practice-based research project developed in parallel with the live Choreomusical work, Jinn. Impetus for Jinn-Ginnaye came from experiences of censorship when the Interational Society of Electronic Arts (ISEA) conference was held in Dubai in 2015, and all images of womens' bodies had to be removed from public presentations. Jinn-Ginnaye asks how the constraints of Islamic culture can lead to new forms of creation and expression.

Jinn-Ginnaye is an exploration of movement in place. It is a collection of dance pieces exploring issues of bringing western dance performance to the United Arab Emirates, where local modesty laws influence how women can be shown in public. The pieces use video compositing, motion capture, and Virtual Reality techniques to remove the body of the dancer, but leave behind the dance, and the traces of the desert in which it was created.

The Jinn project was initiated by Carlos Guedes is interested in exploring the unique sounds of movement in the desert surrounding Abu Dhabi. He had been experimenting with methods of capturing the sound of wind across the dunes when he noticed how various forms and densities of sand created vary different sounds as he walked through them. In order to explore this further, Guedes invited a number of dancers to go out into the dunes with him, and they experimented with the best forms of movement to create sound. While I was in Abu Dhabi to make a site-specific motion capture piece for the ISEA 2014 conference, Carlos invited me to take one of my inertial motion capture suits into the desert so we could capture both the sound and the movement of a dancer in the desert.

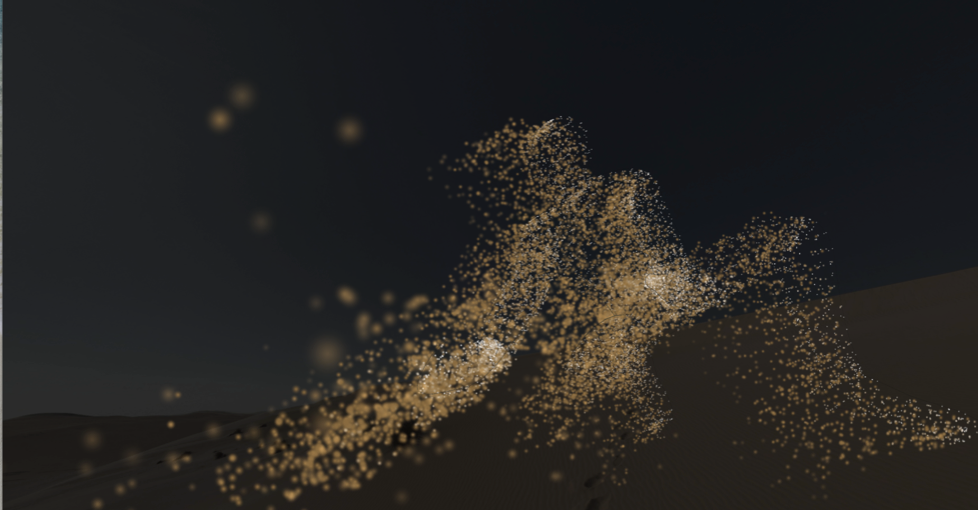

United Arab Emirate modesty laws place restrictions on depictions of the human body in public. I decided to use the UAE restrictions as a creative tool, and developed software to create a “sand dancer” which would not offend our hosts in the UAE, but would tap into local legends of Jinn, and the older Ginnaye linked to the term Genius Loci, or spirit of a place. The sand dancer needed to reform and scatter – taking human form only long enough to be recognized, then blowing like sand in the desert wind.

Over the course of 2 years, we built up a collection of audio, video and movement recordings together with a 360 spherical images of the capture locations. I developed custom software using the Unity3D game engine, Google Cardboard, Samsung Gear VR and the Oculus Rift DK2 to place these sand dancers in the middle of the middle of the Rub Al Khali desert. Through these VR tools, we were able to and to allow audiences to instantly travel to one of the most inhospitable locations on the planet, and meet a representation of the spirit of the place.

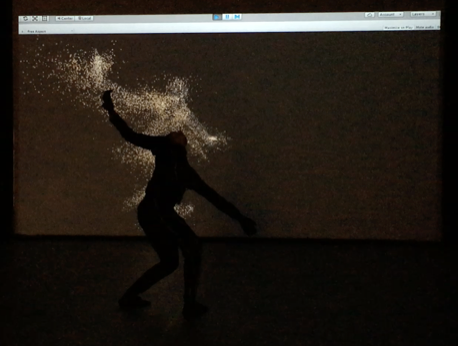

During performances of Jinn in Abu Dhabi, audiences saw a live dancer perform in front of a video projection filmed in the Rub Al Khali desert. After several performances, we distributed Samsung Gear VRs, and iPhones with Google Cardboard viewers. We put the dancer into an inertial motion capture suits and performed a sand dance where the dancer’s movements were transmitted to the VR viewers and the audience could see her projected in 360 degree stereo into the remote location. The audience reported that the VR viewers gave the performance a more immediate context. They felt a clearer, stronger, link to the original location after viewing it in VR, but none of the audience members watched the entire performance in the immersive environment. They all chose to take off the 3D viewers, and watch the live dancer with in front of them. Two audience member reported that the sand dancers felt like a gimmick when viewed through the VR display, but viewing the desert location through the VR goggles changed their experience of the whole performance. They felt a greater degree of presence. Their experience of the performance was enhanced by this new form of photography, but they felt the presence of the live performer was stronger when she stood on the stage in front of them.